The following is an interview with Shaykh Muḥammad ʿAlī Girāmī Qummī, a well-regarded mujtahid and teacher of the Qumm seminary. Shaykh Girāmī has also become well-known in the past few decades for his inspired istikhārahs, which he regularly conducts in person and by telephone after the maghrib and ʿishāʾ prayers. Born in the year 1317 S.H. (1938 C.E.), he hails from a line of esteemed scholars; his grandfather, the late Shaykh Abu al-Qāsim Kabīr al-Qummī, was among the foremost scholars of Qumm who resided and taught in the city’s seminary even before the arrival of Shaykh Abd al-Karīm Hāʾīrī’s in the year 1301 S.H. (1922 C.E.). Shaykh Girāmī was a student of some of the foremost scholars of the 20th century, including Sayyid al-Burūjirdī, Imām al-Khumaynī, Sayyid Muḥaqqiq Dāmād, Shaykh Murtaḍā Hāʾirī Yazdī, and Shaykh Farīd Arākī.

The following interview was conducted at the end of 2016 by a French sociologist studying the various social and religious functions of the practice of istikhārah. In it, Shaykh Girāmī explores the nature of the istikhārah, a sanctioned means by which a believer consults God when facing a difficult or perplexing decision. Shaykh Girāmī explains the spiritual grounds of the istikhārah, the various methods of conducting it, and how a seeker should understand and approach it in terms of his decision-making process. The transcript was first published in the Persian-language monthly, Taqrīrāt, and is translated and reprinted here with permission. (Click here for the original Persian-language transcript.)

What is an istikhārah? Is it just a way of seeking the grace and blessings of God?

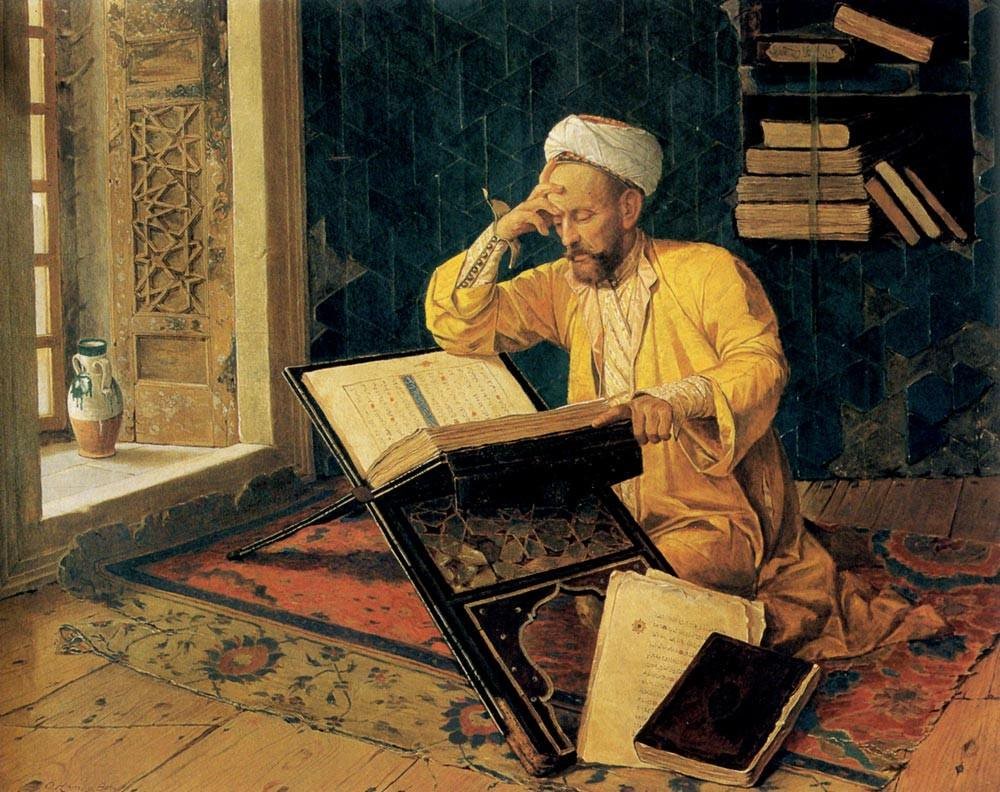

Istikhārah is of two types: the first is a prayer to attain something desired, which is the [literal meaning of istikhārah, namely] “seeking what is good,” from God. The second type is a means of consulting God, so that He may show us the path that leads to the preferred decision. This second type can be conducted either by means of the Qurʾan or a tasbīḥ (rosary). We have religious evidence that justifies both forms of istikhārah. We know that humans are quite frequently stuck at a crossroads, and must decide and choose how to act. If they are undecided after having reflected deeply and consulted others, they can seek an istikhārah. For example, one can do an istikhārah for a marriage prospect, for an important business transaction, or even for accepting an important responsibility. The istikhārah is a miracle of and a blessing from the Ahl al-Bayt for their Shiʿah during the occultation of the twelfth Imam, and allows them to make good decisions.

On what issues do people request you to conduct an istikhārah?

People will seek an istikhārah for all the various types of issues they may face, issues they cannot resolve or make a decision about on their own. And they see its beneficial results; why else would they continue to seek istikhārahs? I have even had a case where someone sought an istikhārah in a judicial matter, where the judge could not decide which way to rule, and he then turned to an istikhārah. After we conducted the istikhārah, and told him that he has misunderstood the facts of the case, he refrained from his issuing his judgment, went back, reviewed his notes, and saw that what the istikhārah had stated was correct. He was really elated. Afterward, he even came and told us the results of his findings. [Translator note: The istikhārah in this case was not with regard to the judgment itself, since istikhārah is not a valid basis for such a judgment, but rather for the judge’s confidence in his own diligence.]

Did the Prophet Muhammad and the Imams also seek istikhārahs?

Istikhārah is only meant to remove one’s doubt and indecision in a situation. The Prophet and the Imams had access to the wellspring of revelation, and they had access to the unseen (ghayb). They had no need for an istikhārah. They did, however, encourage their followers to seek it; we have numerous reports that the Imams would teach their followers when and how to do istikhārahs, through the Qurʾan, a tasbīḥ, or by other means. But we don’t have any evidence that the Imams would seek an istikhārah for themselves.

Some Christians, particular within the Orthodox churches, will use the Bible to seek an istikhārah. But why do Sunnis not utilize the Qurʾan in this way?

Sunnis have yet to fully benefit from the Qurʾan. They have not benefited fully from the Prophet himself. The Prophet had so many elite companions, but they source so many of their laws and sharʿī rulings in the words of Abu Ḥurayrah, who despite having only spent approximately a year and a half with the Prophet, narrated around 30,000 aḥādīth directly from him. It is even narrated of the second caliph that he severely castigated Abu Ḥurayrah for his extensive fabrication of hadith.

Yet nowadays, many Sunnis, both within Iran and abroad, have sought istikhārahs. A little while ago, a delegation of scholars from the region of Sistan visited and requested a number of them. Even some Christian priests from Tehran have requested istikhārahs.

Is there a preferred time for seeking an istikhārah?

Some say that one such preferred time is Friday afternoon after the midday prayers, among other reported times throughout the week. However, these types of reports seem to not be supported by any religious evidence. The correct view is that God is always listening; His door is always open. My own teacher, ʿAllāmah Ṭabāṭabāʾī, would tell me that he does not accept there to be a preferred time for istikhārahs, and neither do I.

What is the correct intention for seeking an istikhārah?

The person seeking an istikhārah, in his heart and mind, must be in a state of indecision. This is a sufficient prerequisite. He doesn’t need to explicitly state his intent.

What things should a person refrain from seeking an istikhārah for?

If we have consulted others, have not found any definitive intellectual or legislative decree, and are still truly confused about how to deal with a situation, we can seek an istikhārah.

Some Qurʾans indicate the response of the istikhārah, that is, a particular page is labelled as “good,” another “bad,” and another “in-between.” Why are these Qurʾans not used for seeking istikhārahs as frequently anymore?

The istikhārah is not like the other Islamic sciences, like fiqh and usul [al-fiqh], nor like medicine and philosophy; it is not a purely intellectual endeavor. The istikhārah is at its core a matter of spiritual emanation; that is, it is a spiritual connection to the unseen. When such a spiritual connection must be established, universal or automatic answers are void, as are definitive yes’s or no’s indicated at the top of a Qurʾanic page. First, all Qurʾanic verses are fundamentally good. Second, each situation has a particular emanation that is relevant to the verse that appears, a particular relationship that the verse may not have with other events. Some of the proof-texts for the istikhārah from our Imams state the following: ما وقع في قلبه, meaning that we must be attentive to what occurs to our heart. And such occurences are of course not uniform.

So do you consider it incorrect to use such Qurʾans?

Yes.

How can lay people conduct an istikhārah themselves? Can they conduct an istikhārah through the internet or telephone?

The command (by the Imams) to conduct an istikhārah is general, and applies to all. However, the only conclusive and determinative istikhārahs are those conducted by a person who has received an inner permission, whether in a dream or while awake. Even a very knowledgeable scholar may not have been ordained with such a permission. In fact, it is said that Shaykh ʿAbd al-Karīm Hāʾirī would not conduct istikhārahs through the Qurʾan, because he would say, “I don’t know nor understand istikhārahs conducted through the Qurʾan. For example, what should I think of a verse that states ‘[Prophet] Musa (ʿa) said…?’ Is it a positive or a negative sign?” He would, however, conduct istikhārahs for himself and others via the tasbīḥ. The istikhārah is really an example of that spiritual emanation, and requires one to have an inner connection and permission.

So are you saying that one should not conduct istikhārahs by internet or phone?

No. As I mentioned earlier, the istikhārah is a spiritual state that is rooted in one’s deeper connection with the unseen. We cannot expect just anyone to have such a connection.

Can ordinary people conduct istikhārahs through translated Qurʾans?

No. Nor can one even conduct an istikhārah via Arabic Qurʾans. Nor is it possible for just anyone to conduct. It really requires that spiritual connection with the unseen.

Is it required for a person to act according to the results of an istikhārah?

It is not mandatory; however it is abhorrent to go against the results. The person has sought to consult God; he should not then oppose His advice. In this regard, the istikhārah is akin to dream interpretation, for not anyone can interpret dreams correctly, nor does it require a certain level of scholarship. There was, in fact, an illiterate woman in Najaf who could interpret dreams. A scholar once asked her how she acquired this ability. She responded, “I was very poor and sought the intercession of Haḍrat ʿAbbās. I saw a dream where they told me to hold a tasbīḥ, and that they will tell me what to say in response to people’s dreams.” She used to say that someone would just whisper in her ear. Therefore, it really has no connection to knowledge or scholarship. It is really a connection to the unseen.

Is it correct for someone to seek multiple istikhārahs with a single intention?

It is not good to repeatedly seek (for the same decision). The first istikhārah is really the criteria (for decision-making).

Then why do so many people do this sort of repetitive istikhārahs?

They are mistaken. If I find out that a person has already sought an istikhārah for a single intention and issue, I will not conduct the istikhārah.

Can you describe how you conduct istikhārahs?

It cannot really be explained. It is one form of connecting with God.

Is there a specific method of teaching or conducting istikhārahs among religious scholars?

Our narrations state various methods for conducting the istikhārah, some of which are mentioned in the Mafātīḥ [al-Jinān]. However, this is all just on the outer aspect of the matter. What is important is that inner spiritual connection, which a person may be inspired with in ways that differ from those mentioned in the texts. God can inspire a person in many different ways; He states in the Qurʾan that even the honeybee receives some form of revelation.

Is the istikhārah related to the science of Qurʾanic tafsīr?

To an extent, it is. Tafsīr functions as a necessary introduction to istikhārah; however the istikhārah is not merely a form of tafsīr. A single verse may result in one istikhārah and have a particular interpretation, which may be different from the interpretation of that same verse in another istikhārah. Because of how quickly the istikhārah takes place, some have said about me that I don’t even look at the words of the Qurʾan.

What is the difference between fortune-telling and an istikhārah?

Fortune-telling is really an attempt to prophesy the future. It does not help a person determine what he should do. An istikhārah, however, helps a person decide how to act. It is for a person who does not know which decision to make. In this respect, an istikhārah is like a doctor’s prescription. It is not good to use the Qurʾan to tell one’s fortune. We actually have narrations that proscribe such uses of the Qurʾan.

Do you also seek istikhārahs for your own decisions?

Yes, of course. Very often. For example, I conducted one this morning. I conduct istikhārahs for certain meetings.

Did you conduct an istikhārah for this interview?

I may have conducted an istikhārah for today’s interview.