Shaan Rizvi

The Shīʿī community in North America, from its earliest years, founded a number of organizations to provide institutional support for the community’s array of needs and goals. Many of the earliest founded institutions continue to exist today, though in an evolved form. This is the first in an installment of Occasional Papers that will explore the roots and developments of some of the community’s important institutions and projects through the eyes of the some of their prominent participants. In this issue, we begin the series with the ḥawzah in Medina, NY, as remembered by its head from 1988-1997, Shaykh Amir Mukhtar Faezi.

˚ ˚ ˚

By the grace and blessings of Allah (swt), on September 1, 2014, during a formal ceremony at the Baitul Ilm masjid, the Chicago Shīʿī community inaugurated the Ahl al-Bayt Islamic Seminary and welcomed its first batch of incoming students.

The Seminary’s classes are currently taught by three esteemed faculty members and scholars of the Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Qūm: Shaykh Amir Mukhtar Faezi, Sayyid Sulayman Hassan and Shaykh Rizwan Arastu. The inaugural class consists of nine students, including five traditional-track and four alternative-track students. In the current semester, the students are studying Ṣarf (Arabic morphology), Naḥw (Arabic grammar), Fiqh, Tajwīd, and Kalām. Further, the Seminary’s curriculum is accredited by, and largely mirrors, the curriculum and texts taught in the Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Qūm.

During the week, the students begin their day with Fajr prayers in congregation. Thereafter, students partake in three hours of classes, with a short break in between each. After classes, students generally return home or take a short break, and reconvene later in the day at the masjid for mubaḥathah—a tradition of the ḥawzah in which students take turns presenting course material and quizzing each other as a means of reinforcing their learning.

Unbeknownst to many, the idea of opening a ḥawzah in North America is not an entirely novel project for the Shīʿī community. Rather, it is a project with a ten-year pedigree and one that has been planned for and conceived of for much longer. In the mid-1980s, a group of committed believers established a ḥawzah by the name of Jamīʿat Walī al-ʿAṣr, in Medina, New York, a small town of about 6,000 people located halfway between Rochester and Buffalo. Although the ḥawzah did not last in that location long-term, some of the most prominent ʿulamaʾ of the Shīʿī community today, including but not limited to Shaykh Ali Abdur-Rasheed, Shaykh Usama Abdulghani, Shaykh Muhammad Ali Baig, and Shaykh Jaʿfar Muhibullah, are graduates of Jamīʿat Walī al-ʿAṣr.

Earlier this year, al-Sidrah sat down with the Shaykh Amir Mukhtar Faezi—Chairman of the Ahl al-Bayt Islamic Seminary and one of the founders of Jamīʿat Walī al-ʿAṣr—to discuss the history of the ḥawzah in Medina, as well as the lessons he gleaned from the experience and hopes to apply in the new Ahl al Bayt Islamic Seminary.

˚ ˚ ˚

Transcript (lightly edited for clarity and content)

Q: Why did you decide building a ḥawzah in North America was important? What led up to that decision, and when did that happen?

A: It was [in the] mid-1980s when the Shīʿah community started realizing that it needs homegrown religious leaders and religious scholars, because the community’s activities were growing and there were not a sufficient number of scholars available to meet those activities. The community was inviting scholars from overseas. These scholars, when they would come, had language and cultural barriers, and their outlook toward American society was different from what was in the minds of community organizers. Our community leaders understood that if we want to move forward, we need local leaders who know the local needs and local culture, who can lead our children to become proud Muslims, and at the same time, productive and positive Americans. And this would happen only if we have homegrown scholars. Because the message received by overseas scholars was kind of putting people off from getting involved in any local community [affairs]. Their message was “No” to almost everything; they only [instructed] people to come and pray and do religious rituals, and they had little else to offer the community. The community was looking for direction on how they should they lead their lives, what they and their children should do, etc. So that was the point at which the community realized it needs leaders who are local and can understand the local issues and offer direction.

As a coincidence, at the same time, a senior ʿālim from Pakistan, who was a very missionary ʿālim and the head of the Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Pakistan, Sayyid Safdar Hussain Najafi, realized that our community members [in Pakistan] were migrating to Western countries; and if they didn’t have local scholars, then it would be difficult for them to keep their future generations in the proper Islamic tradition. So the late Sayyid Safdar Hussain Najafi started this effort of establishing at least one ḥawzah in England. He started that in early 1980s and for five or six years he put in effort, but his efforts were not very fruitful. While in England, he met with a zākir by the name of Sayyid Jaan Ali Kazmi. Sayyid Kazmi told Sayyid Safdar, “I know a group of Shīʿah community members in the Buffalo area who have the facility and willingness to do something, but they really don’t know what to do. So if you go and talk to them, maybe they will be happy to do this project, since you’re not finding anything [productive] in England.” Sayyid Safdar went ahead and applied for the visa and came on his own initiative to Medina, New York, where he met the father of Sayyid Sulayman Hassan, Dr. Sayyid Sirajul Hasan Abidi, who was the President of the Islamic Center of Medina at the time. Through Dr. Abidi, he met other community leaders. Sayyid Safdar gave them the idea that since you have a building, funds, resources, etc., it will be good if you establish a ḥawzah here and train local scholars, since it is difficult for scholars back home to obtain a visa and come here; and in addition there is the problem of language and culture, so if you have local scholars it will be more helpful for your future generations. The idea kind of took root in the minds of these people. It was 1986 when the decision was made to have a ḥawzah in Medina. It took one year to begin. The first classes of this ḥawzah were started in 1987. The first student of the full-time ḥawzah was an African-American by the name of Ali Abdur-Rasheed. He was a convert from a Christian family in Buffalo. He was lead to the Shīʿī path by the Iranian students studying at the University of Buffalo about 2-3 years before joining the ḥawzah. These were the after-effects of the Islamic revolution, where, at university campuses, those curious young minds who were exploring the religion of Islam, some of them got interested in Shīʿī Islam.

Ali Abdur-Rasheed was the first full time student, and then there were some high school students who came from practicing families in New York, New Jersey, Washington, upstate New York, etc. They were brought in to Medina with the understanding that they would go to Medina Public High School, and in [the] evenings they would get religious classes. So, they would do both things together. Their parents felt that if their kids leave these big cities and the social environment and pressures there—if they came instead to Medina, which is a village with only a population of 6,000—the environment would be much better, simpler and overall a natural and good environment away from all those social evils [of big cities]. The idea was that they would get their religious classes in the evenings so that when they graduated from high school, they would have a good background in religious studies, and later on, wherever they go to college or university, they would become future community leaders. Even if they became accountants or doctors, they would serve communities and provide religious guidance and leadership. Two in one. People would work and provide religious services on an honorary basis to the community. That was the idea when this started.

Q: What is your part in this story? How did Medina, NY develop?

A: The inspiration for the ḥawzah in Medina, Sayyid Safdar Hussain Najafi, was my teacher, and when he came back to Iran, I was a senior student in Qūm. He told me that the time had come when I should leave, go to America, and be the head of this ḥawzah. He told me this in 1986, but I had to wind up my studies. I asked him for one year—give me one year and then I’ll go. So, I thought I should at least get my basics. I was preparing myself for Pakistan. I had no idea I’d end up going to America. So let me at least take some basic courses in English and learn about American society. Also, I had just gotten engaged, and I had to marry, so I asked him to let me complete this process. He granted me one year. In 1988, I applied for the visa in Pakistan and I was granted the visa. It was October 1, 1988, when I came to Medina. It was the month of Ṣafar, and almost a day or two before Arbaʿīn. In this one year, when I was getting ready, four scholars came one after the other [to Medina] to serve, and on average, they stayed for 3-4 months. It was so difficult living in a very small village with very basic facilities, working with American kids. Scholars were not used to working with this age group with this background, and also so far away from any social life.

When I came, I realized within a few weeks, that actually this system of “two in one” was not going to work. So my suggestion was that if you want to have these high schoolers, if you want them to have religious training, we can have them. But we cannot hope that these people can be religious leaders of our communities. I said we need full time students who are done with high school at least. So we started looking for the full-time students. After Ali Abdur-Rasheed, the next student was one half-native, half-white brother named Yusuf Ahmad from Indiana. He was our second student, who got his bachelors from Indiana State University. He had taken some Arabic during university and converted during college. He had married a woman from Malaysia. He came as a Shīʿī Muslim. Now that we had these two students, we started actively looking for full-time students with at least a high-school diploma, preferably with some college background. We started contacting community leaders by phone and mail all over North America, and started traveling to different conferences, etc. At that time, there were 2-3 conferences taking place throughout the year. There was MSA-PSG, and then Imam-e-Zamana Foundation used to hold an annual conference in Washington DC. The Shīʿī youth and activists came to these conferences, and we would set up booths at these conferences.

Additionally, the impact of the Islamic revolution in Iran on youth in this part of the world, especially in religious families, created a lot of interest in going to ḥawzah and pursuing Islamic studies. There were many people, with different ages and backgrounds, who were very interested in going to ḥawzah in Iran and learning and studying and serving Islam and spreading a similar message everywhere. At that time, the Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Qūm was not ready to accept students from this part of the world, so these individuals were left with no options. These students tried to approach their local ʿulamaʾ in the major cities and ask if they would provide classes. Some of them were able to get some informal kinds of classes in their own cities. But since it was not formal, and none of these ʿulamaʾ were able to offer the full package of Islamic studies in a traditional way, it did not go a long way. People were still waiting for an opportunity where they could go to a formal ḥawzah and study there full-time. So when word came out that there was a ḥawzah in Medina which was accepting students, all those who were waiting for this opportunity jumped and headed toward Medina. There were a large number of African-American families who came. It was actually one large group, which had migrated from North America to Central America and had been living in Central America for some time, largely in St. Croix. They had slowly started moving back to North America. They had also become Shīʿahs. If they were not fully Shīʿah, they were impressed by the Shīʿī tradition and were interested in knowing it more and were open to exploring it and looking into it.

The first individual who came from that group was Idris Samawi Hamid, when he did his Bachelors from, I believe, from Syracuse University. Idris had converted formally to the Shīʿī tradition in the University. He was very close to Irani, Lebanese, Iraqi students. He came to Medina, and through him the group got the news that there is a ḥawzah. The next family that came and brought many people was Marhūm Dr. Karim Abdulghani, the father of Shaykh Usama Abdulghani. Dr. Karim, as a physician, was a prominent member of that group, very intelligent and sincere. He came with his family, purchased a home in Medina, and himself became a student and brought all his family members to the ḥawzah as students. His wife, sons, daughters, himself — everyone became students. Then he had three or four brothers-in-law, and their relatives. So this is how their whole group heard about it and started coming in. In addition to them, we got students from North Carolina, the first of whom was Jaʿfar Muhibullah, who came as a fresh high school graduate. Through Jaʿfar Muhibullah, some other students came from North Carolina.

Similarly, news reached California and we got a number of students from the Los Angeles convert community who were all African-Americans. And we got a few from Georgia. Down the road, we got some Caucasian students as well. We had a student from Oregon, named Abdul Noor, who came from Oregon, and he married an African-American girl from the local Shīʿah Muslim community. We also had a few African-American students from Maryland. We got other students as well—Caucasians, Iranians, Afghanis, Lebanese, people from the East African Khoja community, and some Indians and Pakistanis. We started with one student, and within a few years we had 30-plus students. It was beyond our ability to manage because we used to provide them a place to live and basic expenses through a stipend.

Q: So how did the community in Medina deal with absorbing these individuals? Was there interaction? I’m envisioning racial and class tension.

A: The local community in Medina, our Shīʿah community, was very diverse to begin with. Our center was in Medina, but our community included people from a 40-50 mile radius, including Niagara Falls, Buffalo, Rochester, and even up to Utica in upstate New York. We had Iraqis, Iranians, Indians, Pakistanis, East Africans. Normally, when a community is small, it accepts diversity and the people are welcoming. Yes, some people had a concern in the beginning because the large number of African-Americans was a totally different kind of phenomenon. But, I, as a leader of the community, played a very active role in making it acceptable to the community, and told them that our model should be the community of the Prophet. I didn’t let people take their developed communities of Iraq, India, or Pakistan as a model. I was successfully able to take the model of that developing community of the Prophet [to] Medina [, NY]. And that is why everyone had acceptance and tolerance. It worked well. And our students, those who remained there with us, were also trained in diverse cultures, they were accepting of change, they were well-behaved, responsible, and community and family-oriented. So we never had any issues or problems. Actually many of our converts were better faith-wise, practice-wise and community-wise than those people who had been Muslim for generations. Their level of taqwa, piety, ḥijāb, integrity, and responsibility, were really very good.

Q: In the beginning you mentioned that Qūm was not able to absorb this Western student population. So did you have a relationship with Qūm, either formal or informal? And how did the African-American students who later went to Qūm transition?

A: Initially when we started the ḥawzah, it had no link with Qūm. But, a ḥawzah in [the] Shīʿī tradition cannot exist and continue without the blessings of the mother ḥawzahs in Qūm and Najaf. That is how the system is. You have to have some link and some deference and acceptance. So, soon I realized that we needed to develop that link. So I started writing to Grand Ayatullahs, Sayyid Al-Khuʿī in Najaf, and Sayyid Gulpāygānī in Qūm. I explained that we have started this work in this part of the world, and we needed their blessings. But, since it was a ḥawzah in America under those circumstances, Qūm and Najaf were very cautious and reserved in giving their blessings, because they were unsure who was behind the project. So there was no cordial response or formal link for the first few years, between 1989 and 1991.

After three years of constantly writing letters, and using some help from our senior ʿulamaʾ in Pakistan, we were able to at least open [some lines of communication] and [convince them] that it was a genuine effort. When time came for the first batch [of students to graduate], we started communicating with the Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Qūm, [saying] that since we were not able to provide a very high quality and comprehensive education for our students due to the lack of resources, staff, and facilities, these students will be lost if they do not get into Qūm and perfect their studies and improve their weak areas. Knowledge is very dangerous when you don’t have it properly and fully. A half ʿālim is a dangerous thing. So, we used this as an argument and convinced the scholars in Qūm that they should consider giving admission to our students. So al-ḥamdu lillāh that worked and Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah Qūm agreed to accept our students.

The first batch that went to Qūm for their studies was Ali Abdur-Rasheed, Munawwar Hasan Ali, Jaʿfar Muhibullah, and Usama Abdulghani. I believe it was 1994 when they went to study there. Then we sent some sisters to study there in Jāmiʿat al-Zahrāʾ. The Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah of Qūm, after meeting our students and talking to them, became convinced that these people are sincere in their studies and have done good work. They may not be very strong in some academic areas, but they are very strong in their sincerity, character, piety and taqwā. They are really good students. And that is why from the very beginning, there is a very high appreciation and respect for our students. Ḥawzah ʿIlmiyyah Qūm always gives these students selected priority. They know that these are special students.

Q: So there was never a full sponsorship, but there was a pipeline system, correct?

A: Yes. And we were the one who applied for [the students’] visas through our ḥawzah. We purchased their air-fare [with] the help of our sister communities in North America. We rented the places over there for these students to live in. We gave them basic necessities to begin their lives over there. For some months, we provided a stipend for them to live over there until they got settled. This was all through the help of our local community and sister communities in North America.

Q: Just one or two more questions. Were you the only teacher in Medina, or were there others?

A: There were times when I was able to bring someone to help me. But no one was able to stay in Medina. Life was very difficult, you had to be a missionary to stay there. Because mainly, there was no social life for your family or children. If any ʿālim was ready to come, his wife and children were not ready to come. And no ʿālim would come without his family. The living conditions and benefits provided were not any incentive, and the work was very hard. Because you were doing ḥawzawī work of Najaf and Qūm with students in America who had no idea what they were doing. And the people in the community who were helping with the project, they were not deeply familiar with the ḥawzah, but they wanted to tell you what to do. There was a lot of pushing and pulling. People wanted to make it like Harvard or better than Harvard, even thought the budget of the janitors in Harvard was better than the budget of our entire ḥawzah.

The expectations of our ḥawzah were very high. People thought that after four years, a student from our ḥawzah should be better than one who had studied in Najaf or Qūm or India or Pakistan for 20 years. So every graduate should be reciting Qurʾān like Abd al-Bāsiṭ, and he should be an encyclopedia of Islamic knowledge, and he should be pious like Salmān al-Farsī, and he should be a very competent leader like Imām Khūmaynī, and he should be a speaker like Rashīd Turābī. Whereas our students came with no background at all, and had only one man teaching the entire group everything, so it was impossible. And that is why several ʿulamaʾ who came got frustrated and left within months. So I ended up just doing it by myself. And later on, some of my senior students were helping me. Ali Abdur-Rasheed, Muhammad Baig and some of the other fourth-year students used to help teaching the younger students.

Q: How did the financial situation work? You said you provided rent, stipend?

A: The major funding came from our local community in Medina, which included the communities in Rochester, Buffalo and the surrounding areas. So there were about 30-40 families, and many of them were physicians. And these were all senior established physicians, and they were making a good amount of donations every year, so most of our budget came from here. But since it was the first such project of the nation, we were receiving funds from Toronto, including NASIMCO (North American Shīʿah Ithna Asheri Muslim Communities Organization). That was another major supporter. Then there were individuals who believed in this project from all over the States. From almost every state, we had a few donors who used to send their khums. At that time, a donation of $2,000 was a big amount. There were about 20-30 individuals in the entire country who would send that kind of money. And NASIMCO would help a little more. Our budget was about $10,000-12,000 per month. We kept things basic and provided all the basic necessities. Salaries and stipends were very low, but people were happy and content. We had two big buildings. The places to reside in were mainly our own. So, for single students, we would give them rooms which they would share. And for married students, we’d give them an apartment, which were also our own. I never had a car for all those 10 years. I lived in Medina with my family and never owned a car. Everything was in walking distance. Many students also never owned a car. Life was very simple and basic.

Q: In the end, what happened? It closed up at some point, what were the reasons for that? Ultimately, what came of this enterprise for the convert community nationwide? Socially, what do you see this ḥawzah made an impact on and what do you foresee in the future in terms of what the new ḥawzah will be doing?

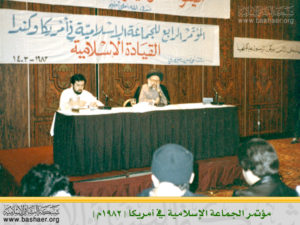

A: While we were operating the ḥawzah in Medina, though we were very small, we were known everywhere in the Shīʿī world. At least the ḥawzahs and the major Shīʿah organizations knew that there was something going on in Medina under the name of the ḥawzah. And whenever one of those people would come to this country, they would come and visit us. For example, the sons of Sayyid Khūʿī, when they came to visit and were establishing Al-Khoie Foundation in New York, they drove from New York City and came to visit us in Medina. The president of the World Foundation, when he came to visit the US, he came all the way to visit us. And the Presidents of African Federations of Khoja Jamaats came all the way and visited us in Medina while they were in the America. If any Iranian or Iraqi ʿulamaʾ came to America later on, they came to visit us. So we were a place a visited by leaders and scholars all over the world if they were in America, and even by the local leaders in America.

Everyone who visited had the same suggestion – a project like this should not be in a village of 6,000, it should be in one of the major cities. There, you can get the issue resolved of the social life of the teachers. If you want to expand, you need more teachers. But if you are in any major city, and there is a community and social life, teachers won’t mind coming there. Your pool [of resources] will also become bigger. Here, you are relying on 30-40 families as your major economic support, but if you go to a major city, you will have a bigger pool and more resources, and the exposure will be [greater] for students, who will see variety of Shīʿah activities, scholars, centers, etc. So that was the advice we got from everyone. We were convinced, but since we had started this [in Medina], we wanted to at least reach to a level such that we could take our successful model somewhere else. We decided we would continue for at least 10 years, and graduate two batches of students, and after that, then we would go to a major location. As 10 years were coming to an end, we started looking actively in North America for moving. The options were Toronto, Los Angeles, New York and Washington DC. And all of these locations had their merits, but we felt that Virginia/Washington area would make a better location. So we wanted to go there. We started making some arrangements, but there is an Iranian center there in Potomac, Maryland. The ʿālim there, Dr. Sayyid Hijazi, when he heard we were moving there, sent us the message that they were in the process of establishing a ḥawzah there. We felt that two ḥawzahs in once place would be too much, plus they had resources, and we didn’t have that kind of resources. So we cancelled that plan and looked into other major cities. I used to visit these cities every year during Muḥarram and Ṣafar, so I had some idea [about them]. Finally, I thought Chicago would be a better place for the ḥawzah. It is in the center of the country. It is a big city, but the activity of the Shīʿah community was not at the level of LA, NY or Toronto. It was a big and mature community, but the activity was not as much, [meaning] you could add something. So, this is why I selected Chicago.

I closed everything in Medina in 1997. I moved in January 1998 to Chicago, with the idea that I would establish a more formal ḥawzah based on all those experiences, which we learned in Medina, with proper facilities, where you have trained staff, sufficient teachers, funds and without interference of those who have no background in the project. However, we realized that before we go about a ḥawzah, we first need a center, our own masjid, our own base, our own following, our own support, and when we have that, then we could start a ḥawzah. And those things took almost 15-16 years to start, first from my own basement, and then in rental places, and then by buying a new building, and then by building a multipurpose building. But now we’re starting a new ḥawzah, and hopefully this ḥawzah will be formal and fully equipped with what we need.